A few conflicting trends can be seen in society today. Over the past few decades, we have been a part of an unprecedented acceleration; one of technology, productivity and output, material consumption, pace of life, depression, and loneliness. Is all of that “forward” movement good? Or is it even movement at all?

Ross Douthat, in “The Age of Decadence,” argues that “the feeling of acceleration is an illusion, conjured by our expectations of perpetual progress and exaggerated by the distorting filter of the internet[.]” This American ideal that the future will be always be better is actually quite recent, and unique.

The peasantry in medieval Europe would not have such beliefs, but rather thought of a past in which Christ’s redeeming qualities were more than the abstractions described by the clergy. Even Renaissance writers described the exalted classics of Ancient Greece and Rome, believing that they would never be matched by their contemporary work. In this age, ironically when compared to today, only in the Islamic World did the future look bright, with scientific and literary advancements coming at a breathtaking pace.

When the transition from a hunter-gatherer society to an agrarian one occured, common wisdom says that this shift heralded a new age in which Humanity had finally began conquering the world. But it really wasn’t so for the average human alive. In fact, historians might argue that civilization conquered humanity.

This transition from a scavenger way of life instead resulted in a dramatic reduction in overall quality of life. While at times there was a surplus of food, farming became a monoculture; surviving on only one or two staples and their diets faltered on the front of diversity. People became stuck—attached to their land—and with that, imprisoned by the very crops they sought to domesticate. This lack of freedom became suffocating to culture and community.

Our modern culture may have removed the shackles of agriculture, but in that process, it put on the yoke of technology and in recent years tightened the reins.

Technological progress has continued to accelerate, or has it? In recent years it seems that progress has slowed; we’ve reached the peak, arriving at an unbreakable glass ceiling. Moore’s Law has broken down, it seems like every new innovation is only the tiniest bit of change from the previous generation. No lone individual can innovate within a field; it instead takes an interdisciplinary team to do so, as we’ve exhausted the possibilities and reached the limits of individual human expertise.

But there is still hope. Marques Brownlee compares this to cars, asking the question, “Are we at peak car?” Answering this shines a glimmer of light on a future where, despite stagnation, society can continue to grow.

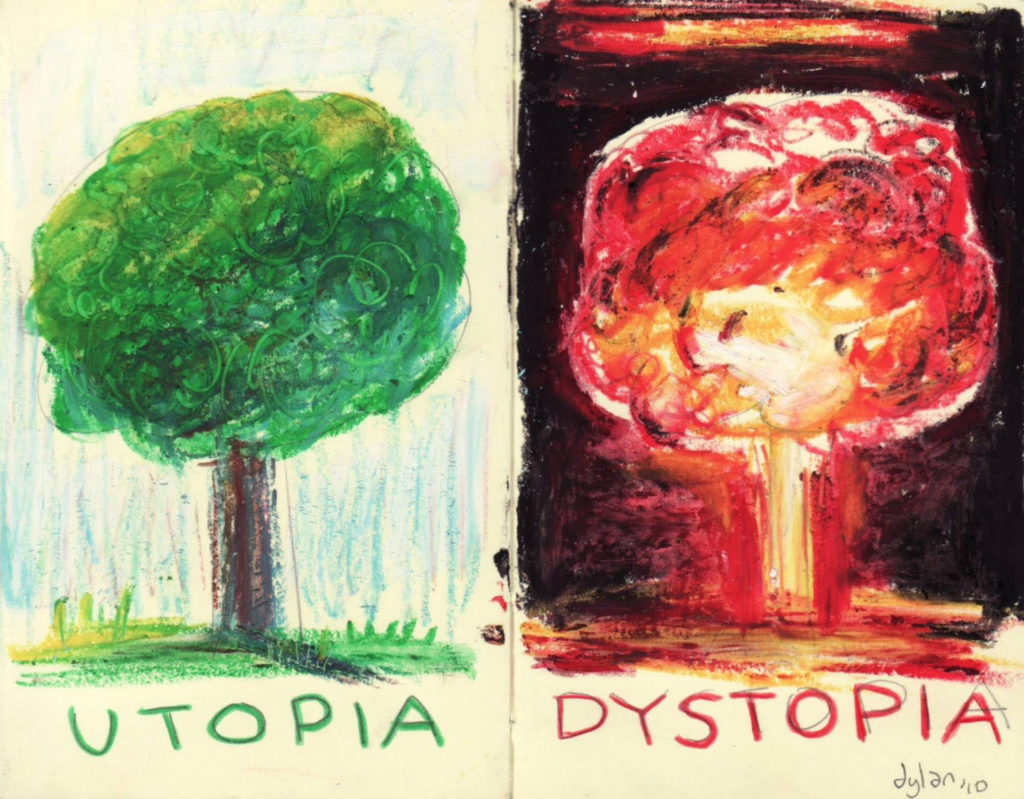

All of these, taken into the context of society at large, have thus far resulted in a breakdown of our future outlook. Society at large has moved from thinking of the future as utopia to dystopia. The enormity of this change in outlook is reflected in our popular literature.

[W]e are aging, comfortable and stuck, cut off from the past and no longer optimistic about the future, spurning both memory and ambition while we await some saving innovation or revelation, growing old unhappily together in the light of tiny screens.

Ross Douthat

It is that gloomy light that now illuminates our thoughts as we drift off to a spiteful sleep. In the elite ranks, even the notion of sleep is frowned upon. After all, it only detracts from productivity and constant output. Ironically the elite work longer hours than ever before, and it is now the middle class that works less and less. This isn’t laziness; rather they can’t. The elite have broken up middle class jobs into component pieces and taken away any semblance of skill, leaving little behind. What scraps are left are handed out to the cheapest labor, and the remaining high level management is reserved for the elite. The mundane jobs left have therefore no path forward; no future outlook where those employed can work their way up the corporate ladder.

It is because of this economic stagnation that Douthat argues that society today has entered into a period of decadence.

The word “decadence” is used promiscuously but rarely precisely. In political debates, it’s associated with a lack of resolution in the face of threats. . . . In the popular imagination, it’s associated with . . . gluttony, . . . and chocolate strawberries. Aesthetically and intellectually it hints at exhaustion, finality — “the feeling, at once oppressive and exalting, of being the last in a series,” in the words of the Russian poet Vyacheslav Ivanov.

But it’s possible to distill a useful definition from all these associations. Following in the footsteps of the great cultural critic Jacques Barzun, we can say that decadence refers to economic stagnation, institutional decay and cultural and intellectual exhaustion at a high level of material prosperity and technological development. Under decadence, Barzun wrote, “The forms of art as of life seem exhausted, the stages of development have been run through. Institutions function painfully. Repetition and frustration are the intolerable result.” He added, “When people accept futility and the absurd as normal, the culture is decadent.” And crucially, the stagnation is often a consequence of previous development: The decadent society is, by definition, a victim of its own success.

Ross Douthat

Key to Douthat’s argument is that “decadence is a comfortable disease.” Society is doing fine.

With this stagnation comes social torpor. America is a more peaceable country than it was in 1970 or 1990, with lower crime rates and safer streets and better-behaved kids. But it’s also a country where that supposedly most American of qualities, wanderlust, has markedly declined: Americans no longer “go west” (or east or north or south) in search of opportunity the way they did 50 years ago; the rate at which people move between states has fallen from 3.5 percent in the early 1970s to 1.4 percent in 2010. Nor do Americans change jobs as often as they once did. For all the boosterish talk about retraining and self-employment, all the fears of a precarious job market, Americans are less likely to switch employers than they were a generation ago.

Meanwhile, those well-behaved young people are more depressed than prior cohorts, less likely to drive drunk or get pregnant but more tempted toward self-harm. They are also the most medicated generation in history, from the drugs prescribed for A.D.H.D. to the antidepressants offered to anxious teens, and most of the medications are designed to be calming, offering a smoothed-out experience rather than a spiky high. For adults, the increasingly legal drug of choice is marijuana, whose prototypical user is a relaxed and harmless figure — comfortably numb, experiencing stagnation as a chill good time.

Ross Douthat

To me, it seems that the averages are deceiving. Younger people are increasingly mobile, and less likely to set down roots in one area and stay long term, even if that’s what they desire. The elite are constantly in search of better opportunities. While it is the middle class, where “forced leisure,” i.e. unemployment as a result of increasingly elite skills needed, keeps them stuck.

Yet recently, a countermovement has emerged; a resurgence of age old ideals of humanity. It seems to be something that only the elites embrace; the middle class once again left behind. One can argue that that embrace is only superficial. Ultimately, the race is ongoing; people aren’t willing to step out as much as they are to slow down and relax, in effect preparing for the final sprint. One that might not ever come.

A century from today, what will this age be remembered as? An age of decadence? The precursor to dystopia? Or the beginning of a long and comfortable decline; a society ultimately on its way to a gradual death?

[T]rue dystopias are distinguished, in part, by the fact that many people inside them don’t realize that they’re living in one, because human beings are adaptable enough to take even absurd and inhuman premises for granted.

Ross Douthat

I can’t help but think, how close are we to the Hunger Games? But Douthat counters: decadence doesn’t necessarily lead to dystopia.

[Decadence], to be clear, [is] hardly the worst fate imaginable. Complaining about decadence is a luxury good — a feature of societies where the mail is delivered, the crime rate is relatively low, and there is plenty of entertainment at your fingertips. Human beings can still live vigorously amid a general stagnation, be fruitful amid sterility, be creative amid repetition. And the decadent society, unlike the full dystopia, allows those signs of contradictions to exist, which means that it’s always possible to imagine and work toward renewal and renaissance.

Ross Douthat

Dossier

“The Age of Decadence,” by Ross Douthat, February 7, 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/02/07/opinion/sunday/western-society-decadence.html

“Are we at Peak Smartphone,” by Marques Brownlee, January 31, 2020. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-DtSrdh5dHU

“The case that America’s in decline,” by Sean Illing, February 28, 2020. https://www.vox.com/policy-and-politics/2020/2/28/21137971/the-decadent-society-ross-douthat-book

“Sapiens,” by Yuval Noah Harari, 2015.

“The Meritocracy Trap,” by Daniel Markovits, September 2019.

Zubin

One of your most engaging articles yet! I truly felt your point when I realized that I have been tricked by the very illusion you talk about! Great work, and keep it up!

Sahil

Thanks!

When I first wrote the article in early March, right before the quarantine was instated, I felt that Douthat’s arguments were really quite convincing. To me, the key to his argument was that “. . . the decadent society, unlike the full dystopia, allows those signs of contradictions to exist, . . . .” While Douthat uses that narrowly, I think it is fundamentally true amid a society rife with complexity and nuance.

Now in hindsight, I realize that this decadence obscured the underlying issues. We became so complacent with life as is, that we never took the time to combat the deeper issues that undersign society. Looking at the silver lining of the COVID-19 pandemic, we now have a better understanding of our society’s limitations. I hope that we can use this opportunity of reflection to welcome change for the future.