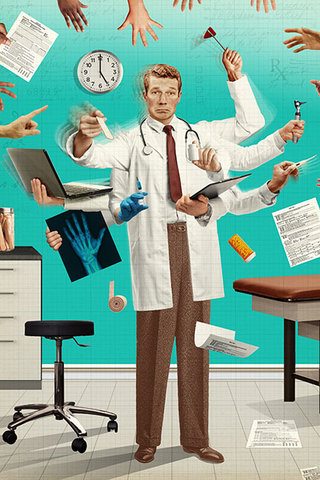

Given the extreme shortage of primary care physicians in the United States, it’s no surprise that patients are more and more being seen by nurse practitioners or physician assistants. While virtual visits and tele-health were slowly rising, the COVID-19 pandemic greatly accelerated their acceptance by patients and healthcare providers alike. The primary care office, therefore, is ripe for disruption and change. Laura Landro invites us to imagine a new future of primary care:

After uploading data from your home blood pressure monitor and electronic scale, you get a call from your health coach to talk about getting more exercise. To help with anxiety issues, you schedule a virtual visit with your mental-health social worker. When it’s time for an in-person checkup, you head to the clinic to be evaluated by the nurse practitioner or physician assistant. And it’s all covered by your health plan.

The traditional experience of getting health care is shifting away from the solo doctor with limited time to spend with each patient and few incentives to promote wellness. Instead, in the future, patients will be more likely to see a team of health-care professionals whose compensation is linked to keeping patients healthy. That team may be led by a doctor, but with a growing shortage of physicians, a nurse practitioner is increasingly likely to be in charge. Patients will also receive more care virtually and in nontraditional settings such as drugstore clinics.

Laura Landro

At first glance, it may seem to be a pleasant future—one without the long wait times and hassles of trying to cram in a year worth of ailments into a 20 minute visit with a primary care physician. Upon deeper thought, however, it becomes clear that not only does this imagined future require patients to continue coordinating their own care between an even greater number of offices, but it also requires them to see a multitude of different providers and specialists to take care of them.

Caring for patients where each aspect of the body is treated completely separately often leads to miscommunication between providers, incomplete and ineffective care, and overlooked concerns. It also requires more travel, more coordination, and more collaboration between disparate teams with incompatible systems.

Imagining a future in which technology “optimizes” healthcare into an assembly line where patients are shuffled from one area to another is not at all appealing. However, there is still some hope. Many providers are experimenting with other approaches to healthcare.

Although a majority of primary-care doctors work for large health systems, independent doctors are forming their own networks or testing new approaches to offering care. Some are creating so-called direct primary care practices that bypass insurers and charge patients a monthly fee—a more affordable version of concierge medicine. Doctors are also linking up with retail clinics. Over the next five years, Walgreens Boots Alliance and VillageMD plan to open 500 to 700 physician-led clinics attached to Walgreens drugstores in 30-plus markets. Their teams will include pharmacists, nurse practitioners and physician assistants; patients will get custom care plans, annual wellness visits and 24/7 access to providers via telemedicine.

LAURA LANDRO

While it may add some convenience that patients can be seen at different times and places according to their own schedule, it is not conducive to effective healthcare. But this issue should not be addressed by technology allowing people to come in whenever they want, but rather by better and more flexible workplace policy that more easily allows employees to visit healthcare providers, care for their children and families, and better transportation systems that allows people to easily get around to wherever they need. Solving these root problems will immediately improve the healthcare of the entire population.

Medicine is about treating patients as human beings. Let’s bring that attitude into every aspect of policy-making.

The key is to get away from a system of paying providers a fee for each service, and only for in-person visits. The federal Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services and private insurers are moving closer to value-based purchasing such as paying providers a fixed monthly fee per patient for a range of services, often with incentives for better managing diabetes, heart disease, asthma and other chronic ailments.

LAURA LANDRO

This method, when used carefully, can help bring down the administrative costs of healthcare. But it can also be used to game the system, as I’ve written about in the past and thought about extensively while doing research into developing metrics for free clinics in Worcester.

A future in which primary care is provided in non-traditional settings, for example at walk-in retail clinics, urgent care centers, and virtual appointments, is disjointed. It invites important information to go unnoticed. Disjointed care increases the administrative costs, as each individual care center must maintain some amount of overhead. Instead of consistent staffing, patients bounce back and forth between providers. Patients don’t benefit, but insurance and healthcare companies do.

Modern medicine has become so large in scope that it is simply impractical for one stand alone family medicine physician to be adequately trained and able to treat the immense variety of symptoms and diseases that patients present with. Therefore, specialists are necessary.

My work in producing short films for the Admissions Department taught me the importance of relying on the expertise of others. I think that there are many parallels between the film industry and medicine. I found that just as a director leads the filmmaking team of camera operators, lighting specialists, sound specialists, editors, actors and actresses, a physician leads the healthcare team of specialists, nurses, and other providers. Both are responsible for guiding their team towards a shared vision, one a completed film, and other the complete care of a patient. There is a need for a physician to guide patient care.

Physician groups have pushed back against removing restrictions on nurse practitioners and physician assistants. The American Academy of Family Physicians, for example, contends that there is no equivalency between a doctor and someone who isn’t one, and that patient safety requires doctors to be in the lead in medical teams, to step in if patients have complex problems or there is uncertainty over treatment.

LAURA LANDRO

Given the 14 year training process for physicians, it is clear that “there is no equivalency between a doctor and someone who isn’t one. NP and PA training is more limited in scope and is focused on treating patients rather than acutely understanding disease processes and the science behind them. Physicians’ training is built on the old ideal of nosology, and is founded on the idea that physicians diagnose and nurses carry out the physicians orders. This certainly isn’t meant to disparage nurse practitioners or physician assistants, many of whom perform some of the same roles as physicians. In fact, most tasks that physicians perform do not require their level of training, especially with the increased administrative burden of modern medical practice.

I envision two potential scenarios for the future of medical education.

The first is that, given the severe shortage of primary care physicians, medical schools and residency positions will begin to open up more seats and expand their programs. In fact, this is already happening. The American Association of Medical Colleges reports that since 2002, allopathic medical schools have increased enrollment by 31 percent. When combined with osteopathic medical schools, which have been growing astonishingly quickly, overall medical school enrollment is up by 52% in the same time period.

A lot has been written about the importance of the physician’s “touch.” Humans need physical contact in order to comfort one another. Touch is an incredibly important way to understand the body, and physicians use touch often to help diagnose problems and comfort patients. Unfortunately, with the rise of diagnostic imaging, we are moving away from this. Virtual healthcare makes this shift even more pronounced.

This was a constant discussion point in my human factors of medicine and medical writing courses. Modern medical students are more reluctant to touch the patient. This inhibits creating an effective patient-physician relationship.

The second potential future, which I think is far more likely, is that primary care physicians will be replaced by primary care nurse practitioners and physician assistants. Many states already allow both nurse practitioners and physician assistants substantial autonomy in treating patients without the supervision of a physician. More states are likely to follow.

As medical schools become more and more competitive and specialist salaries increase while primary care physicians salaries remain stagnant, the individuals who are motivated to study through medical school will almost all specialize. Therefore medical school applicants will self-select to become specialists. Those that do want to practice primary care will look elsewhere. Rather than becoming a “doctor” with an M.D. degree, they will instead pursue other healthcare pathways and become nurse practitioners or physician assistants.

This future will mean that medical school will continue to become more and more competitive, with increasing MCAT scores, GPAs, and extracurriculars. It will completely shift the way that medicine is practiced and doctors will be even more focused on diagnosing diseases and less on treating the patient as a person.

the problem is that we are creating jobs that overlap significantly in their roles, but with different training requirements and standards

if someone wants to become a nurse, which is a completely separate profession that involves a focus on patient care, they should be able to do so

it’s an important profesion with it’s own specific requirements for what it needs

if someone wants to become a physician, which focuses on treatment and management of diseases, they should be able to do so without artifiical barriers to prevent them from doing so.

if someone wants to be doing the role of a physician, they should not first need to become a nurse and then later do all of this additional training to be ale to be a physician without having the ufll responsibility

Imagining a future in which physicians look at patients as puzzles to be solved and where disjointed technology replaces a physician’s visit does not seem at all appealing. Instead it is pushing doctors even further away from primary care because they are left with the task of administration and not patient care. The reason that most physicians go into medicine is because medicine is about treating patients as human beings.

Ultimately, both solutions are stopgap measures. The actual solution is to increase the number of residency positions available, reduce administrative costs and overhead, and proportionally increase the compensation of primary care physicians so that it becomes more attractive than other specialties.

The solution is to make medical education more inclusive less competitive and remove unnecessary steps like the MCAT and VITA, or at least make them less unnecessarily difficult for the purpose of “weeding people out.” Allow the same people who would otherwise be nurse practitioners to instead become physicians and gain even training and more breath of practice

All together, these solutions allow more people to become primary care physicians. We all benefit from that.

Dossier

“The New Doctor’s Appointment,” by Laura Leandro, September 9, 2020. https://www.wsj.com/articles/the-new-doctors-appointment-11599662314

“U.S. Medical School Enrollment Surpasses Expansion Goal,” July 25, 2019. https://www.aamc.org/news-insights/press-releases/us-medical-school-enrollment-surpasses-expansion-goal

“Where Can Nurse Practitioners Work Without Physician Supervision?” October 26, 2016. https://online.simmons.edu/blog/nurse-practitioners-scope-of-practice-map/

“The Primary Problem,” by Linda Keslar, January 27, 2020. http://protomag.com/articles/primary-problem