I can only say that I am incredibly impressed by the controller and his professionalism, guidance, and calmness. Wow!

Given the extreme shortage of primary care physicians in the United States, it’s no surprise that patients are more and more being seen by nurse practitioners or physician assistants. While virtual visits and tele-health were slowly rising, the COVID-19 pandemic greatly accelerated their acceptance by patients and healthcare providers alike. The primary care office, therefore, is ripe for disruption and change. Laura Landro invites us to imagine a new future of primary care:

After uploading data from your home blood pressure monitor and electronic scale, you get a call from your health coach to talk about getting more exercise. To help with anxiety issues, you schedule a virtual visit with your mental-health social worker. When it’s time for an in-person checkup, you head to the clinic to be evaluated by the nurse practitioner or physician assistant. And it’s all covered by your health plan.

The traditional experience of getting health care is shifting away from the solo doctor with limited time to spend with each patient and few incentives to promote wellness. Instead, in the future, patients will be more likely to see a team of health-care professionals whose compensation is linked to keeping patients healthy. That team may be led by a doctor, but with a growing shortage of physicians, a nurse practitioner is increasingly likely to be in charge. Patients will also receive more care virtually and in nontraditional settings such as drugstore clinics.

Laura Landro

At first glance, it may seem to be a pleasant future—one without the long wait times and hassles of trying to cram in a year worth of ailments into a 20 minute visit with a primary care physician. Upon deeper thought, however, it becomes clear that not only does this imagined future require patients to continue coordinating their own care between an even greater number of offices, but it also requires them to see a multitude of different providers and specialists to take care of them.

Caring for patients where each aspect of the body is treated completely separately often leads to miscommunication between providers, incomplete and ineffective care, and overlooked concerns. It also requires more travel, more coordination, and more collaboration between disparate teams with incompatible systems.

Imagining a future in which technology “optimizes” healthcare into an assembly line where patients are shuffled from one area to another is not at all appealing. However, there is still some hope. Many providers are experimenting with other approaches to healthcare.

Although a majority of primary-care doctors work for large health systems, independent doctors are forming their own networks or testing new approaches to offering care. Some are creating so-called direct primary care practices that bypass insurers and charge patients a monthly fee—a more affordable version of concierge medicine. Doctors are also linking up with retail clinics. Over the next five years, Walgreens Boots Alliance and VillageMD plan to open 500 to 700 physician-led clinics attached to Walgreens drugstores in 30-plus markets. Their teams will include pharmacists, nurse practitioners and physician assistants; patients will get custom care plans, annual wellness visits and 24/7 access to providers via telemedicine.

LAURA LANDRO

While it may add some convenience that patients can be seen at different times and places according to their own schedule, it is not conducive to effective healthcare. But this issue should not be addressed by technology allowing people to come in whenever they want, but rather by better and more flexible workplace policy that more easily allows employees to visit healthcare providers, care for their children and families, and better transportation systems that allows people to easily get around to wherever they need. Solving these root problems will immediately improve the healthcare of the entire population.

Medicine is about treating patients as human beings. Let’s bring that attitude into every aspect of policy-making.

The key is to get away from a system of paying providers a fee for each service, and only for in-person visits. The federal Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services and private insurers are moving closer to value-based purchasing such as paying providers a fixed monthly fee per patient for a range of services, often with incentives for better managing diabetes, heart disease, asthma and other chronic ailments.

LAURA LANDRO

This method, when used carefully, can help bring down the administrative costs of healthcare. But it can also be used to game the system, as I’ve written about in the past and thought about extensively while doing research into developing metrics for free clinics in Worcester.

A future in which primary care is provided in non-traditional settings, for example at walk-in retail clinics, urgent care centers, and virtual appointments, is disjointed. It invites important information to go unnoticed. Disjointed care increases the administrative costs, as each individual care center must maintain some amount of overhead. Instead of consistent staffing, patients bounce back and forth between providers. Patients don’t benefit, but insurance and healthcare companies do.

Modern medicine has become so large in scope that it is simply impractical for one stand alone family medicine physician to be adequately trained and able to treat the immense variety of symptoms and diseases that patients present with. Therefore, specialists are necessary.

My work in producing short films for the Admissions Department taught me the importance of relying on the expertise of others. I think that there are many parallels between the film industry and medicine. I found that just as a director leads the filmmaking team of camera operators, lighting specialists, sound specialists, editors, actors and actresses, a physician leads the healthcare team of specialists, nurses, and other providers. Both are responsible for guiding their team towards a shared vision, one a completed film, and other the complete care of a patient. There is a need for a physician to guide patient care.

Physician groups have pushed back against removing restrictions on nurse practitioners and physician assistants. The American Academy of Family Physicians, for example, contends that there is no equivalency between a doctor and someone who isn’t one, and that patient safety requires doctors to be in the lead in medical teams, to step in if patients have complex problems or there is uncertainty over treatment.

LAURA LANDRO

Given the 14 year training process for physicians, it is clear that “there is no equivalency between a doctor and someone who isn’t one. NP and PA training is more limited in scope and is focused on treating patients rather than acutely understanding disease processes and the science behind them. Physicians’ training is built on the old ideal of nosology, and is founded on the idea that physicians diagnose and nurses carry out the physicians orders. This certainly isn’t meant to disparage nurse practitioners or physician assistants, many of whom perform some of the same roles as physicians. In fact, most tasks that physicians perform do not require their level of training, especially with the increased administrative burden of modern medical practice.

I envision two potential scenarios for the future of medical education.

The first is that, given the severe shortage of primary care physicians, medical schools and residency positions will begin to open up more seats and expand their programs. In fact, this is already happening. The American Association of Medical Colleges reports that since 2002, allopathic medical schools have increased enrollment by 31 percent. When combined with osteopathic medical schools, which have been growing astonishingly quickly, overall medical school enrollment is up by 52% in the same time period.

A lot has been written about the importance of the physician’s “touch.” Humans need physical contact in order to comfort one another. Touch is an incredibly important way to understand the body, and physicians use touch often to help diagnose problems and comfort patients. Unfortunately, with the rise of diagnostic imaging, we are moving away from this. Virtual healthcare makes this shift even more pronounced.

This was a constant discussion point in my human factors of medicine and medical writing courses. Modern medical students are more reluctant to touch the patient. This inhibits creating an effective patient-physician relationship.

The second potential future, which I think is far more likely, is that primary care physicians will be replaced by primary care nurse practitioners and physician assistants. Many states already allow both nurse practitioners and physician assistants substantial autonomy in treating patients without the supervision of a physician. More states are likely to follow.

As medical schools become more and more competitive and specialist salaries increase while primary care physicians salaries remain stagnant, the individuals who are motivated to study through medical school will almost all specialize. Therefore medical school applicants will self-select to become specialists. Those that do want to practice primary care will look elsewhere. Rather than becoming a “doctor” with an M.D. degree, they will instead pursue other healthcare pathways and become nurse practitioners or physician assistants.

This future will mean that medical school will continue to become more and more competitive, with increasing MCAT scores, GPAs, and extracurriculars. It will completely shift the way that medicine is practiced and doctors will be even more focused on diagnosing diseases and less on treating the patient as a person.

the problem is that we are creating jobs that overlap significantly in their roles, but with different training requirements and standards

if someone wants to become a nurse, which is a completely separate profession that involves a focus on patient care, they should be able to do so

it’s an important profesion with it’s own specific requirements for what it needs

if someone wants to become a physician, which focuses on treatment and management of diseases, they should be able to do so without artifiical barriers to prevent them from doing so.

if someone wants to be doing the role of a physician, they should not first need to become a nurse and then later do all of this additional training to be ale to be a physician without having the ufll responsibility

Imagining a future in which physicians look at patients as puzzles to be solved and where disjointed technology replaces a physician’s visit does not seem at all appealing. Instead it is pushing doctors even further away from primary care because they are left with the task of administration and not patient care. The reason that most physicians go into medicine is because medicine is about treating patients as human beings.

Ultimately, both solutions are stopgap measures. The actual solution is to increase the number of residency positions available, reduce administrative costs and overhead, and proportionally increase the compensation of primary care physicians so that it becomes more attractive than other specialties.

The solution is to make medical education more inclusive less competitive and remove unnecessary steps like the MCAT and VITA, or at least make them less unnecessarily difficult for the purpose of “weeding people out.” Allow the same people who would otherwise be nurse practitioners to instead become physicians and gain even training and more breath of practice

All together, these solutions allow more people to become primary care physicians. We all benefit from that.

Dossier

“The New Doctor’s Appointment,” by Laura Leandro, September 9, 2020. https://www.wsj.com/articles/the-new-doctors-appointment-11599662314

“U.S. Medical School Enrollment Surpasses Expansion Goal,” July 25, 2019. https://www.aamc.org/news-insights/press-releases/us-medical-school-enrollment-surpasses-expansion-goal

“Where Can Nurse Practitioners Work Without Physician Supervision?” October 26, 2016. https://online.simmons.edu/blog/nurse-practitioners-scope-of-practice-map/

“The Primary Problem,” by Linda Keslar, January 27, 2020. http://protomag.com/articles/primary-problem

Health policy is an important way of effecting change in society at scale. When acting at scale, it is necessary to make assumptions and generalizations that do not take into account all of the nuances and complexities of a society that is not inherently equal and just. As a consequence, health policy that may seem effective at first glance may actually be complicit in creating inequities that perpetuate society’s injustice.

Today, the care of patients in hospitals and outpatient clinics, like anything else, is a business. Businesses are focused on efficiency and optimization of profits. It therefore follows that almost all metrics in healthcare are designed from an administrative or billing perspective. However, the institutional bias that results from policy, despite being much more subversive, can be addressed by careful design of metrics, separating compensation from outcomes (at least until a more equitable society is formed).

Navathe and Schmidt show one of the pitfalls of using metrics where the perceived rhetorical purpose to outsiders and perhaps even the designers—improving care for all patients—is mismatched to the practical purpose to hospitals and clinics—optimizing profits. In order for metrics to be effective, it is necessary to consider the possible rhetorical uses of the metrics while designing them.

When metrics are used to determine compensation, people will always attempt to game the system. Instead of allowing physicians to be rewarded for treating patients, they are incentivized to treat their “score.” It would be naïve to assume otherwise. Unfortunately, tying healthcare outcomes to compensation is fundamentally flawed in a society where hospitals can “refuse” to see patients in implicit, less obvious ways.

The byproduct of tying outcomes to compensation and using metrics to quantify outcomes results in a situation where hospital administrators limit “unprofitable services like psychiatry wards either by keeping only a small number of spots for patients or by simply not offering a dedicated psychiatry ward at all.” These metrics “create incentives for hospitals to avoid patients from these groups” because patients in minority populations are “economically unattractive to hospitals.” Chronically understaffing preventative care offices has deep repercussions in the form of worse patient care and increased overall costs over a patient’s lifetime.

With each of these types of payment models, the initial intention regarding social justice may be unclear, unknown or even aimed at promoting it. A value-based payment reform model seems as innocent as a daisy and worlds apart from the most overt forms of structural racism, such as segregated transportation or drinking fountains. Yet, far too often, such models share the consequence of systematically disadvantaging some groups, whether as a result of the design of policies or culturally ingrained behavioral patterns.

Amol S. Navathe and Harold Schmidt

With today’s data-focused society, healthcare metrics are indeed critical tools to assess the functioning of our healthcare system. However, it is important to keep in mind that they have limitations and can easily be flawed Ultimately, metrics must be used with extreme care to ensure that these unintended consequences are fully thought through.

Dossier

“Why a Hospital Might Shun a Black Patient,” by Amol Navathe and Harold Schmidt, October 6, 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/10/06/opinion/medical-racism-payment-models.html

“The Tyranny of Metrics,” by Jerry Muller, 2018.

Popular media, in whatever form it takes, is an incredible resource to analyze the aspirations and goals of a society. It serves as a mirror for its intended audience to look into and can offer a glimpse through a window into another world for those whom it’s not directly aimed at.

When I was 15, I got my first job, as a dishwasher at a pizza restaurant, and on breaks, all my conversations with co-workers eventually turned to the topic of money. We would fantasize about what we would do if we suddenly had it: vacations, cars. In high school, we’d hear rumors that so-and-so was rich, because their parents had a second house or a boat. We all thought that money was the important thing: If you had it, you were “rich” — which for us was indistinguishable from “elite.” If you didn’t, you weren’t.

This was true, to an extent. But it wasn’t the whole story. How did I learn it wasn’t? From television.

Rob Henderson

For Rob Henderson, this reflection was done through television. He spent his early life shuffling between foster homes, eventually joined the military, went to Yale, and is now a doctoral student at Cambridge University. He was able to directly experience the vast differences between social classes in the United States and beyond. This perspective is invaluable.

Like many people, he initially thought that social class was dependent on money. But, “‘The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air’ taught me that it wasn’t,” he posits. This insight into the differences between monetary wealth and “cultural capital,” as Elizabeth Currid-Halkett discusses, shows that each broadly defined social class has its own set of values that are often reflected in the popular media. The fictional stories that Henderson refers to are perhaps less fictional than they might at first seem.

Early on, I thought of television as a window into another world. I would watch it to escape the one I was in, and to learn more about others. Later, though, it became more like a mirror. The more I saw, the more I learned what I wanted; the shows I chose to watch, in turn, reflected my desire to build a better life for myself, and I took my cues from them on how to construct it. Either stay like this, I thought, as I gazed at the TV, or try to live like that.

Rob Henderson

In fact, both Henderson and Currid-Halkett have discussed similar themes in the past.

Strangely enough, as we ascend that ladder, we encounter a fork—it seems that the “elite” definition becomes bifurcated by wealth and education. Currid-Halkett attributes this to the idea of “cultural capital,” which is a separate form of wealth than monetary capital. This is where education plays a significant role.

Paul Fussell argues that the criteria we use to define the tiers of the social hierarchy are in fact indicative of our social class. For people near the bottom, social class is defined by money — in this regard, I was right in line with my peers when I was growing up. The middle class, though, doesn’t just value money; equally important is education.

Rob Henderson

And therein lies society’s strange curve. It seems that for the lower class, i.e. those in the lowest two quintiles of household income, income is the important factor. Increasingly, the middle class is less distinguished by income as it is by education. To enter, a college education—and the ideals that it instills on its students—is a prerequisite. Currid-Halkett provides an example of the English professor, who may not make as much as a self-employed plumber, but would certainly be considered to be of a higher social status. For the upper class, however, an elite college education is necessary.

In College is the New Entry to the Middle Class, I described the dichotomy between the upper class, for example, doctors and lawyers, who still ultimately “trade their time for money” and the upper echelons of the 1%, who instead have money work for them, such as entrepreneurs and executives.

Ultimately, these definitions remain murky and nebulous. I don’t think that we will ever arrive at a particular definition that works across the board. However, I do think that these definitions hint at the evolving nature of the elite who are becoming increasingly obsessed with education and cultural capital. Over time, this obsession is trickling down into the upper and middle classes, resulting in even higher rates of social stratification, and allowing “the slow corruption of American meritocracy” to “[ossify] into a formidable caste system.”

Dossier

“Everything I Know About Elite America I Learned From ‘Fresh Prince’ and ‘West Wing,’” by Rob Henderson, October 10, 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/10/10/opinion/sunday/television-culture.html

“The Meritocracy Trap,” by Daniel Markovitz, 2019.

“In the past, America was not as unequal as it has become,” October 24, 2019. https://www.economist.com/books-and-arts/2019/10/24/in-the-past-america-was-not-as-unequal-as-it-has-become

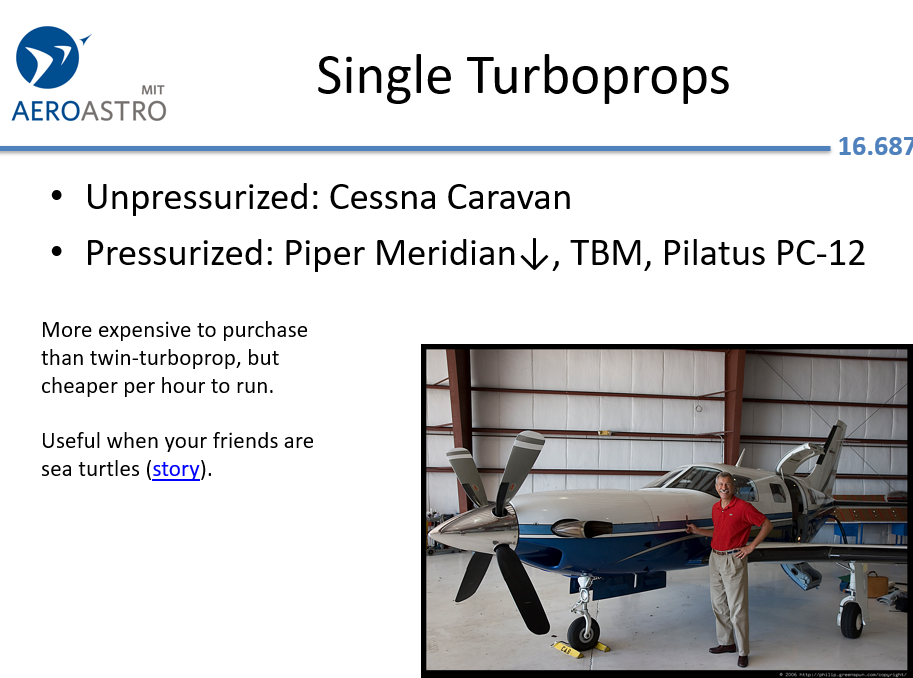

This past January, only a few days after the first reports of COVID began coming out of China, I took part in an aviation class at MIT taught by Philip Greenspun. It was genuinely awesome being surrounded by people equally as passionate about aviation, especially in the local area.

In fact, our discussions significantly influenced the way I look at avionics. Early on in my flight training, I had a sort of “disdain” for modern glass cockpits. I wanted to learn flying on the old-fashioned instrument panel and hone my skills as a manual pilot before beginning to rely on technology later on for safety purposes. Now, I have a more nuanced opinion on the state of avionics, specifically what their benefits and their flaws really are. I wrote about this recently in the context of the new Microsoft Flight Simulator 2020.

But one thing that stood out to me was the slide on sea turtles (two excerpts from the presentation below).

Apparently, critically endangered Kemp’s Ridley turtles journey along the Gulf Stream up the east coast of the United States in the warm summer months for food. However, as the water cools and they begin traveling south, some of the turtles become trapped in Cape Cod Bay and become cold-stunned. These turtles are rescued by volunteers, rehabilitated by the New England Aquarium in Boston, and flown by volunteer pilots to Florida where they can continue their rehabilitation and eventually be released.

I mean, what a cool excuse to go flying!

Only a few weeks later, I began my SCUBA training. While searching for diving related videos, one that popped up was the Devil’s Hole Adventure video from Jonathan Bird’s Blue World. That video absolutely captivated me, combining my interests in filmmaking, diving, expeditions, and education. Almost immediately, I was completely addicted to the show and have since watched almost every episode. It was especially awesome to find out that Jonathan had also gone to WPI and is a Massachusetts native.

Later in the year, Destin from Smarter Every Day released an excellent video on sea turtles. I’m sure you can imagine my excitement! In that video, he and the staff at the Cook Museum transported Kale, an injured sea turtle, from Virginia to the museum facilities in Alabama. In it, the whole team drives Kale, of course, taking some precautions to make sure that his skin remains hydrated and he isn’t stressed from the long journey.

In response to Philip Greenspun’s post on the subject, John V asks why use all of the resources to fly the sea turtles instead of putting them in a van and driving them. Destin and the team at the Cook Museum did something similar for Kale, so it’s well within reason, on top of saving quite a bit of avgas and the ensuing environmental impact. It certainly made me question the entire endeavor. What exactly are the pilots volunteering for?

This question bothered me. Were the benefits of saving a few sea turtles worth the emissions impact of flying? Looking into the subject in more detail, I came across an article from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration that explained why flying is, in fact, a preferable option than driving:

Transports can be stressful for turtles, especially those in poor health. Anything we can do to minimize transport time reduces that stress and increases the chances of successful rehabilitation. Transports can take multiple hours, depending on the destination. Traveling to southern Florida could take 24 hours by ground! That can take a toll on a sick sea turtle, so flying is preferred.

[. . .]

There are huge benefits to using flights instead of ground transportation. Flights reduce transport stress for sick turtles and, hopefully, increase their likelihood of successful rehabilitation. Flights also minimize the staff resources that would be required for a multi-day transport south by vehicle. All resources are stretched thin during cold-stunned stranding season. Rehabilitation facilities need to keep all of their staff and volunteers working on-site caring for cold-stunned turtles and often don’t have the manpower to drive turtles to other facilities.

NOAA

Ultimately, this mission is much more than a good excuse to fly a long cross country. It brings together people from all over the country to help protect an endangered species using the tools at our disposal. It seems that with each passing day, the news we hear keeps getting worse. This is a heartwarming opportunity to make the world a better place.

Getting closer to my pilot license, I thought it would be a wonderful trip to make in the near future and perhaps make it a holiday tradition—if you’re interested in doing this with me, please let me know!

Dossier

“Pilots Help Sea Turtles Take Flight,” June 10, 2019. https://www.fisheries.noaa.gov/feature-story/pilots-help-turtles-take-flight

“Merry Christmas to the Sea Turtles,” by Philip Greenspun, December 25, 2017. https://philip.greenspun.com/blog/2017/12/25/merry-christmas-to-the-sea-turtles/

“Merry Christmas (again) to the Sea Turtles,” by Philip Greenspun, December 25, 2018. https://philip.greenspun.com/blog/2018/12/25/merry-christmas-again-to-the-sea-turtles/

“How Do You Airlift 500 Sea Turtles?” by Rebecca Maksel, May 18, 2015. https://www.airspacemag.com/daily-planet/how-do-you-airlift-500-sea-turtles-180955281/

With the release of Microsoft Flight Simulator, more and more people are getting into aviation—and that’s awesome! It also means that many people, new to aviation, are faced with the daunting task of using modern avionics and glass cockpits.

And that begs the question, do these avionics actually have a good user interface? Or rather, do they simply replicate patterns that pilots are used to.

Look to military aviation, for example, and you’ll see a convergence into heads-up displays. Rather than having advanced avionics that end up distracting the pilot and forcing her to look down at the instrument panel, HUDs allow the pilot to continue keeping her eyes at the sky. The goal is to distill the information into its most useful form for decision making, to provide situational awareness, and to reduce pilot workload and let her focus on more important tasks.

Bringing this ideology into the general aviation space might have a profound impact on the way pilots train and fly.

During my flight training, I purposefully learned and used “old-school” technology to the extent that I could: standard steam gauges, paper sectionals, VOR navigation, and no iPad running ForeFlight.

Certainly there is a safety component that warrants being trained in old-school methods and techniques—and I’m all for it. Ultimately, avionics shouldn’t become a distraction from actually flying.

Dossier

MIT Ground School, by Philip Greenspun, January 6, 2020. http://philip.greenspun.com/teaching/ground-school/

I can’t believe that I hadn’t seen this earlier. Genuinely a fresh take on the writing process!

The word “meritocracy” has come into vogue lately. It seems that our societal ideals that promote ability and equality of opportunity are more so being questioned—not necessarily on principle, but in practice. Bringing these ideals to fruition in a tangible manner will always result in some controversy, because by definition meritocracy creates inequality. But how that inequality perpetuates itself into dynasties is being exposed, for example, in college admissions, among others.

More and more, a college degree is becoming a prerequisite to jobs, not because of the skills or education that it supposedly provides, but because of the cultural capital that it does.

On the tyranny of meritocracy, Michael Sandel summarizes:

We should focus less on arming people for meritocratic combat, and focus more on making life better for people who lack a diploma but who make essential contributions to our society.

We should renew the dignity of work and . . . We should remember that work is not only about making a living, it’s also about contributing to the common good.

Michael Sandel

This is made more true each day that the COVID pandemic drags on. It is increasingly clear that society is completely dependent on people that we would otherwise like to sweep under the rug. Instead, let’s take this opportunity to reward them with more than just recognition as “heroes” that keep our world turning.

In The Economist, it is noted that Markovitz believes that “the idea of meritocracy has validated inequality, because rich and poor alike “earn” their position. Success depends on educational achievement beyond the reach of many, but winners feel they deserve their spoils, while losers are asked to accept their fate. Restoring dignity to workers at the bottom may require the sort of organization and activism that improved their lot a century ago. For some Americans, that upheaval could prove uncomfortable.”

Dossier

“The Tyranny of Merit,” by Michael Sandel, September 15, 2020. https://www.ted.com/talks/michael_sandel_the_tyranny_of_merit

“Rising Education Levels Provide Diminishing Economic Boost,” by Josh Mitchell, September 6, 2020. https://www.wsj.com/articles/rising-education-levels-provide-diminishing-economic-boost-11599400800