It seems that there is a resurgence of old as a countermovement to the unrelenting progress of technology. While it may connect us more quickly and efficiently than anything prior, the pace has become exhausting. Hours of Zoom calls and conferencing can help relieve the lack of social contact, but also contribute to “Zoom fatigue.”

People want a break. Salama argues that writing letters might be a fun way to do so.

After many days of nonstop Zoom calls for work, the last thing he wanted to do was look at another screen to catch up. Plus, he said, writing a letter could be a fun creative exercise to break up the monotony.

So I wrote back. And then I wrote to another friend and another, and lately not a week has gone by when there hasn’t been a letter to respond to. In most of these exchanges, there seems to exist this unspoken code of slightly formal, performative language meant to evoke the past. My childhood friend’s first message, for instance, included a florid analysis of John Keats’s maritime isolation off the coast of typhus-plagued Naples in 1820.

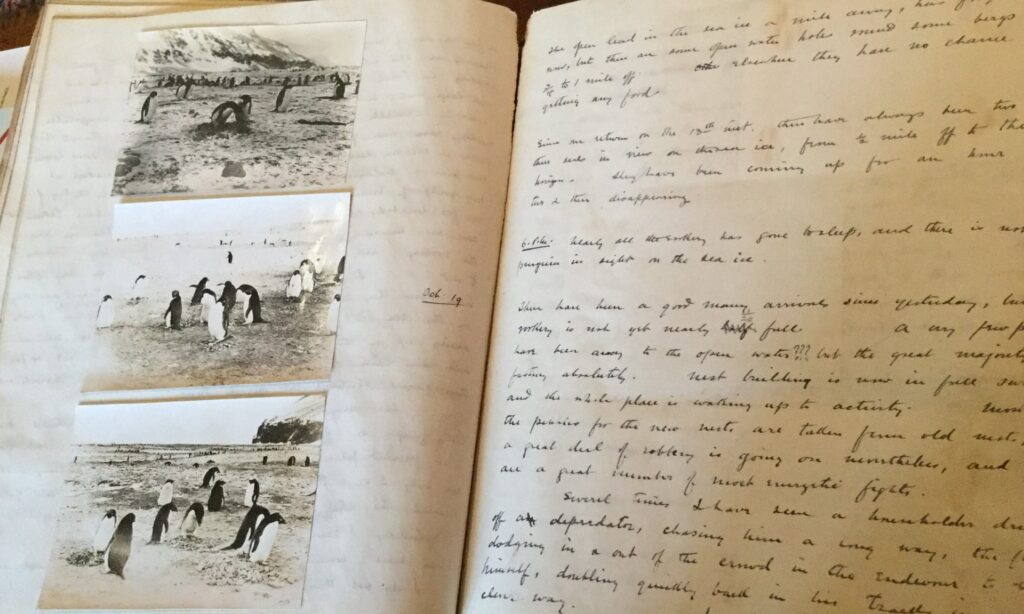

“There’s something about the ambience of the room,” he wrote. “The gentle fire, the nautical aura, the fact that I’m writing a note — it makes me feel like a captain off on an expedition in a foreign land, writing back home.”

It adds to a sense of emotion and escape, yet hardly detracts from the ability to write candidly about our wide range of current experiences.

[. . .]

But like so many other things in this otherwise-terrifying global quarantine, I’ve found writing letters to be wonderful in the simplest of ways. For each one, I sit at our dining room table for the better part of an hour, away from my phone and computer, with only a sheet or two of blank white printer paper in front of me. I’m hardly able to keep a regular journal without it feeling like a chore, but writing to someone else is sending a fresh entry off into the world without ever having to look at it again.

In return, I’ll be left with something far more interesting than a mundane account of my own pandemic days: a patchwork of pages that were sent to me by others, each one fresher than the next.

It’s been deeply comforting to think that whatever I am writing will soon be in the hands of someone else, especially in a time of so much physical distancing. I’ve sent letters as far as Argentina and South Korea, and as near as only a few blocks from my door. Some of the handwriting I’ve seen, like mine, has been laughably illegible; other letters are aesthetically works of art. One friend, an international student isolating on an otherwise-emptied college campus in New Jersey, enclosed a petal from a blossoming cherry tree. In these pages, I read the smiles I cannot see.

Jordan Salama

The romantic idea of the adventures of expedition continues to be something that we dream about. Those with actual experience used to write their “purple prose” in journals and memoirs. Today, these escapades tend to be documented with video—the likes of vlogs and documentaries. Instead of being privy to the minds of the writer and the emotions they experienced, we observe the situation directly. In some ways, this is limiting. We are neither physically present to have the full depth of experience, nor are we able to understand the emotion that the adventurer feels. We are just observers.

Even in scientific writing, where objective observation is still key, when recounting the scientific writings in libraries around the world, we harken back to a day when that observation required some amount of interpretation. We knew that everything was seen through the lens of another person rather than the sterile lens of a camera. Yet, the act of interpretation is now invisible, but very much still there. Instead, the charge now lies solely on the viewer, which leaves it exposed to an unprecedented vastness of minds.

Certainly, in many ways this can be a positive. But we have learned that it can also be a negative. Gatekeepers exist for a reason, and the harsh reality is that we now understand that they do provide some value, i.e. that of expert interpretation to help us recognize and understand the key details amidst a forest of trees.

Cameras for example, have revolutionized science for the better. However, we prize them too much, forgetting that even they are not as objective as we might initially expect (think, aliasing, for example). Partly for this reason I enjoy the cinema—people know that it’s a heightened experience, better than reality. Yet we still have the ability for it to feel very real.

Ultimately, writing letters to one another reminds us of an another age. One where people might have been more connected than we are today, as counterintuitive as that seems.

Dossier

“You Should Start Writing Letters,” by Jordan Salama, July 12, 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/07/12/opinion/letter-writing-coronavirus.html

“When the World Stops, Traveling in John Keats’s ‘Realms of Gold,’” by Frances Mayes, March 26, 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/03/26/travel/coronavirus-essay-mayes-keats.html

“How Whole Foods, yoga, and NPR became the hallmarks of the modern elite,” by Ezra Klein, November 14, 2019. https://www.vox.com/podcasts/2019/11/14/20964420/whole-foods-yoga-npr-elite-ezra-klein-elizabeth-currid-halkett-inequality

Zubin

Great post, however the beginning was a very sharp and confusing.

Sahil

Thanks for the feedback! Not sure exactly what you mean or how I might make it better?