When I wrote my original piece discussing the prescription policy of the free clinics, my primary concern was for patients without adequate access to transportation. I argued for increased scrutiny into the policy because these patients might have been better served with longer supplies of prescriptions. Ultimately, I suggested that implementing better collaboration between the clinics would be a great first step to addressing the larger issue.

In that piece, I did mention the potential for prescription abuse. One form, I explained, was that “patients can game the system, traveling from clinic to clinic to obtain duplicate prescriptions.” While this was not backed up by any specific examples, it was based on anecdotal evidence from my conversations with the clinic leaders and other medical professionals at the clinics.

One form of prescription abuse that I overlooked is the risk of suicide or overdose due to an excessive amount of prescriptions. This is particularly true with psychiatric medications where patients are already at heightened risk. Brian Barnett, in his piece, “The 90-Day Prescription Isn’t for Everyone,” provides a succinct rebuttal to the idea that patients should be given longer supplies of prescriptions, emphasizing that “psychiatric drugs play an outsize role in intentional overdoses.” Therefore, like in the free clinics, he explains that “prescribing conservative quantities to these patients is standard practice” (Barnett 2019).

Do the free clinics follow this same ideology? I wanted to investigate this issue and determine if there is a difference in the number of days of medication given out for psychiatric prescriptions versus others at the Epworth Free Medical Program.

For each instance of a psychiatric prescription between 2014 and 2019, the daily intake of pills, number of pills, and number of refills was recorded. The total daily supply was calculated by dividing the number of pills by the daily intake and multiplying by one more than the number of refills. This resulted in a new metric describing the total number of days of medication prescribed to patients.

total_supply = num_pills / daily_intake * (num_refills + 1)

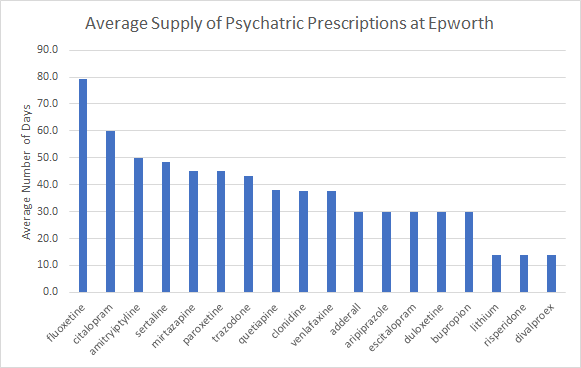

These calculations showed that, on average, providers prescribed 42.9 days worth of psychiatric medication to patients. The breakdown of days by prescription is shown below.

In the future, it would provide an immense benefit to analyze the data in greater detail. For example, we can examine “at risk” patients, defined as having a chief complaint of psychiatric nature or diagnosis of psychiatric nature.

I think this issue warrants extensive discussion to determine the best practice for the free clinics. Maybe the policy currently in place is already the best practice in consideration of these points and those I raised in the earlier piece.

At the end of the day, the general consensus amongst the physicians and providers at the free clinics is that patients should not be given more than 90 days worth of prescriptions. Ultimately, patients should follow up to review their prescriptions, get additional treatment, or get a primary care provider. This should be made easier for patients struggling with transportation Potentially, the clinics can help subsidize a mail pharmacy so patients in need can get their prescriptions through the mail, don’t have to keep picking up new ones, and get only a limited quantity at once.

Note: the fully anonymized data is obtained from an IRB-approved research project at Worcester Polytechnic Institute, under the direction of Brenton Faber, PhD.

Dossier

“The 90-Day Prescription Isn’t for Everyone,” by Brian Barnett, February 6, 2020. https://www.wsj.com/articles/the-90-day-prescription-isnt-for-everyone-11581032892

“Prescriptions and Policy in the Free Clinics,” by Sahil Nawab, December 30, 2019. http://www.sahilnawab.com/wfcc/q4_2019.pdf

“Top 25 Psychiatric Medications for 2016,” by John Grohol, July 8, 2018. https://psychcentral.com/blog/top-25-psychiatric-medications-for-2016/