Most of my training was in a Piper Cherokee 140 with an upgraded 160 hp engine. I used to wonder when entering the designations in my logbook — PA 28 140? P28A 140? What do these numbers and letters even mean?

Author: Sahil Page 2 of 16

Even after taking immunology, this video gave me a better, more visceral, understanding of the immune system!

Dossier

“Generating the Dots vs. Connecting the Dots,” by Sahil Nawab, July 28, 2020. http://www.sahilnawab.com/blog/generating-the-dots-vs-connecting-the-dots/

“The Business Case for Electric Aviation,” by Sahil Nawab, June 18, 2021. http://www.sahilnawab.com/blog/the-business-case-for-electric-aviation/

“The Dilemma of Electric Aviation,” by Sahil Nawab, January 10, 2020. http://www.sahilnawab.com/blog/the-dilemma-of-electric-aviation/

“Electrification of Last Mile Delivery,” by Sahil Nawab, April 24, 2020. http://www.sahilnawab.com/blog/electrification-of-last-mile-delivery/

Beyond the locked gate of the airport, the plane waits patiently out on the tarmac. It’s thirsty for fuel. I punch in the code and push open the chain-link door as it squeals on its tired hinges.

Filling up fuel in your car is typically not a fun activity. But, somehow, it’s different with a plane. Perhaps it’s the fact that the tank is just the inside of the wing — you can see (and hear) quite clearly as the fuel laps up against the edges. I watch the blue tinged fuel slowly creep its way up to the top. As it nears, I slowly let up on the pressure of the filler handle and let the fuel slow to trickle. As the vapors vent, I smell the distinct odor of AvGas.

Climbing under the wing and bracing myself against the wheel, I drain the fuel sump to check for contaminants. I lift up the fuel inspector to the sunlight to check for the characteristic blue tint of the fuel. In the old days, some would simply dump the 50-odd mL of fuel on the ground, but today, conscious of the environment and the rising cost of fuel, most pour it back into their tank, including myself.

During this whole process, a few might even don protective rubber gloves as to avoid touching the fuel. After all, unlike automative gasoline, AvGas — or more appropriately 100 Low Lead (100LL) — is still contains trace amounts of tetraethyl-lead. The additive serves several purposes, including preventing engine knock and detonation as well as for lubrication of valves.

This situation plays out every day at nearly all airports in the United States and the rest of the world. Yet, according to the United Nations Environment Programme in their August 30 press release, “the era of leaded petrol is over.”

As others have pointed out, that’s not exactly the case. The UN EP announced that leaded fuel was finally phased out in Algeria, one of the last holdouts for automotive gasoline. However, leaded fuel in the form of 100LL AvGas is ever-present, exhausted by the light planes flying in the skies directly overhead.

Unfortunately, there currently exist no viable alternatives to leaded AvGas, which has a higher octane rating of 100 compared with the 87 of regular automative gasoline or 93 of premium automative gasoline. Consider also that most planes were designed in the 1950s and remain essentially unchanged in their powerplant designs since then, and the market is ripe for disruption. I think this highlights the need for significant research into developing alternatives that could be a drop-in replacement for traditional 100LL.

Dossier

“Scrap the proposed $1,000 landing fee. Keep general aviation alive.” by Sahil Nawab, June 6, 2021. http://www.sahilnawab.com/blog/scrap-the-proposed-1000-landing-fee-keep-general-aviation-alive/

“Here’s Why Planes Still Fly With Leaded Fuel,” by Mercedes Streeter, September 6, 2021. https://jalopnik.com/heres-why-planes-still-fly-with-leaded-fuel-1847615621

“Era of leaded petrol over, eliminating a major threat to human and planetary health,” August 30, 2021. https://www.unep.org/news-and-stories/press-release/era-leaded-petrol-over-eliminating-major-threat-human-and-planetary

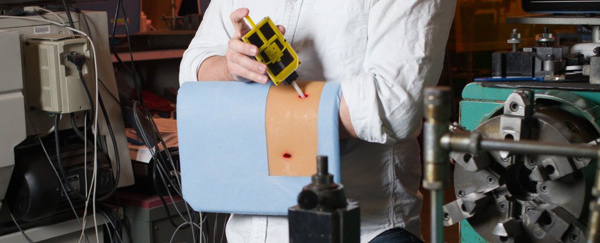

When we think of surgery, the image that most often pops into our heads is the darkened operating room, with a huddle of attendants surrounding the surgeon, all eyes glued to the surgical field. This is what Nikolai Begg, then an engineering student and now engineering director at Medtronic, thought when he first observed a surgery. While this heightened drama certainly is better for the camera and focuses our attention, the real operating room is quite a different scene.

The room is kept cool and bright, with staff bustling around setting up sterile equipment and readying the patient. The anesthesia team wheels the patient in through the double doors, gently talking the patient through what will happen as they get the anesthetic. As the patient goes under, the ventilator is connected, and a heater is switched on around the patient to keep them warm against the cool air of the OR. Eventually things settle down, but the lights do not dim just yet. Instead, the lights above the operating table are switched on and provide a focused beam on the surgical site. A time out is performed, inspired by the pre-takeoff briefing by pilots, to verify the patient and procedure.

THE PHYSICS OF PUNCTURE

Now as the first incision is about to be made, this is a critical moment in laparoscopic surgery. As Begg describes, the whole room quiets down and the surgeon is handed a trocar, essentially a modern version of a bayonet, to make several punctures through the abdomen for the camera and instruments. Begg suggests that we are all familiar with the physics of this — remember trying to stab a straw through a CapriSun juice pouch? Put too much pressure, and the instant it goes through, bam! You get a nice splash of juice all over your hand. Do it very wrong, and you might have a hole on both sides or a hurt hand as well. So imagine the stakes if the puncture is happening right above the abdomen?

Underneath the skin of the abdomen is a thin layer of fat. Beyond this is the peritoneum, similar to a balloon that encloses the abdominal organs. The challenge for the surgeon is to puncture through the peritoneum without going too far and entering the abdominal cavity and unintentionally damaging the anatomy below. In his TED talk, Begg compares this to drilling through a thin wall.

The physics are the same after all, right? When you apply a force towards the wall, there will be an equal and opposite force back towards your hand. Right at the moment when the drill first goes through the wall, however, there’s suddenly an imbalance. The wall cannot apply any force back, which results in the drill accelerating towards the wall until you can react. Begg wanted to solve this problem, and he had an idea.

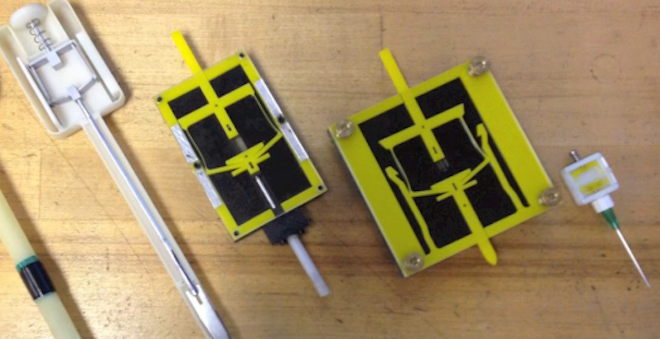

POPSICLE STICKS AND RUBBER BANDS

Nearly eight years later, I too observed a laparoscopic colectomy. At the moment of puncture, I remembered this talk. The scene was the same, but this time, the surgeon was using a modern trocar which automatically retracts just as the puncture occurs. The journey from a simple metal awl to a complicated mechanism started out as a simple model using popsicle sticks and rubber bands.

It goes to show that coming up with a solution for a complex problem can sometimes be as simple as putting together a bunch of popsicle sticks in an interesting and thoughtful way. And by thinking through the physics of puncture, Begg decided to use a spring to retract the tip as soon as it went through. As pressure is put on the tip, it pushes the popsicle sticks outwards, which interferes with the wall and “sticks” through friction. However, as soon as the pressure is removed, i.e. as soon as it punctures, nothing is holding the popsicle sticks in place. The spring is then able to pull back on the tip and retract it before it can damage any structures underneath.

LOOKING FOR THE OBVIOUS

As Begg explained, this had been a serious problem for over 25 years with little change in the trocar device itself. Solving this required looking at it in a different way. Rather than attributing it to the skill of the surgeon, a mechanism could take the guesswork out and react to changes much faster than a human. The genius in this particular device is that it requires no active components and accomplishes the retraction purely mechanically.

Often, it is the most obvious problems that are the most challenging to see. We’re not always aware of them or we take things for granted. By seeing the physics of puncture, Begg was able to find a new solution that seems obvious now in hindsight. Perhaps this will inspire us to look deeper at the world around us, searching for things that we otherwise would have overlooked.

Dossier

“A tool to fix one of the most dangerous moments in surgery,” by Niklai Begg, November, 2013. https://www.ted.com/talks/nikolai_begg_a_tool_to_fix_one_of_the_most_dangerous_moments_in_surgery/transcript?language=en

Note: This article was originally published as part of the Q2 2021 issue of the WFCC Newsletter and is reproduced here with permission. See original: http://www.sahilnawab.com/wfcc/q2_2021.pdf

When I walk into St. Anne’s in the waning light of a summer evening, I often turn myself around at the door looking out towards Worcester. Peeking out over the treetops that line the parking lot are the gleaming buildings of UMass Medical School. In the shadow of the largest medical center in central Massachusetts, literally less than 3500 feet away across Lake Quinsigamond, there is a tremendous need for healthcare.

This stark contrast serves as an ironic backdrop for the volunteers who steadfastly donate their time and energy in service of our community. Without their contributions, the substantial impact of free medical programs would not be possible.

During the pandemic, the entire healthcare system has been on unsteady ground. A number of initiatives have been in place since then to ensure that patients are continued to be cared for, including telehealth services, modified check-in procedures, and appointment based visits. In this issue, we interview Dr. James Ledwith, the medical director of Epworth, about how he guided the program’s efforts to remain open to in-person visits and the challenges the program faced during the pandemic to maintain their ability to see walk-in patients.

Yet we also recognize that there is opportunity for more volunteers to help ensure that our commitment to the community can be sustained through the future. A common refrain amongst free medical programs throughout the country is the need for “dollars and doctors” as well as nurses, case managers, interpreters, and a multitude of other volunteers.

How do we ensure that the free medical programs are sustainable through the future? There are two important steps: (1) ensure that we have enough clinical and administrative volunteers, and (2) get the support of community institutions like local businesses and healthcare organizations. This may involve direct funding through grants, covering the malpractice insurance of providers who choose to volunteer outside of their practice, or by subsidizing essential services that patients require such as labs, imaging or specialist visits.

Beyond this, a number of potential initiatives with community organizations and healthcare partners. For example, some free clinics offer malpractice insurance, but this is a costly proposition. Alternatively, many employers offer coverage if their providers volunteer in the community.

One of the biggest issues facing free medical programs in greater Worcester is the immense need for in-person interpreters. This is a critical way to better connect with patients, who are often immigrants or visiting family members. Having interpreters available allows patients to feel understood, both from a conversational perspective, but also a cultural perspective.

If you are interested in volunteering or supporting the mission of the Worcester Free Care Collaborative, please visit www.worcesterfreecare.org/volunteer for more information or email worcesterfreeclinics@gmail.com.

In a previous issue, we discussed How Stories in Medicine Connect Us. Elizabeth Dunn, a researcher who studies happiness and charity, explains that cultivating a connection with the community is one of the most effective ways to make a strong, positive impact. Volunteering at the free medical programs offers a tremendous opportunity to serve the community and “appreciate our shared humanity.”

Dossier

“The Demand for Volunteer Physicians is Rising The Demand for Volunteer Physicians Is Rising. The Number of Uninsured Is Too,” by Joseph Darius Jaafari, October 27, 2017. https://nationswell.com/demand-volunteer-physicians-free-health-clinics/

“Is There A (Volunteer) Doctor In The House? Free Clinics And Volunteer Physician Referral Networks In The United States,” by Stephen L. Isaacs and Paul Jellinek, May 1, 2007. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.26.3.871

“Making the Most of Free Medical Clinic Experience,” by Rachel Rizal, February 23, 2021. https://www.usnews.com/education/blogs/medical-school-admissions-doctor/articles/how-premed-students-can-make-the-most-of-free-clinic-experience

I will admit that this is quite late. I had most of this written a while back, but my use case has changed over time, as has the software experience, so I wanted to update my thoughts.

With the release of iPadOS and the new keyboard and trackpad case, discussion has been renewed surrounding whether or not the iPad Pro can be used as a laptop replacement. While the capabilities of the iPad have been steadily increasing with each update, this particular one is quite promising for power users and productivity geeks.

However, I think that this discussion misses the entire point of an iPad — it’s not meant to be a laptop replacement, regardless of how Apple markets it. In fact, I would argue that the iPad is powerful because it is not a laptop replacement. It is a secondary device. This is justified by its place in Apple’s lineup and their incredible hesitation to put macOS or full desktop class apps, despite what their ads may show.

It doesn’t really make sense for Apple to want to cannibalize the sales of Macs. However, it is likely that the iPad is significantly more lucrative for them, with a wider profit margin. Plus, being a cheaper device overall, more people might want it as they pivot to a different type of computing experience, which is why if more people start using the iPad as their primary device it might still be a good deal for Apple.

Therefore, I do not see the iPad as a replacement for my laptop. In fact, even though it is one of the most powerful mobile devices, I rarely use it as anything more than a glorified clipboard or piece of paper.

Yet despite being one of the most powerful mobile devices, I rarely use it as anything more than a glorified clipboard or piece of paper. Slowly, I’ve been trying to use it in different ways for more situations.

The biggest improvement so far has been turning Safari into a “desktop-class” browser. This means that I can have multiple Google Drive documents open, with research and webpages side by side.

As students, I think that the iPad Pro has the potential to be a gamechanger. For me, the original intent was to get the iPad just that I could use the Apple Pencil to take notes. It’s always better to take notes by hand because the act of writing helps solidify information into your head, but also the slower pace allows you to distill that information to its most important form.

The very limitations allow this format to succeed. In addition you get the flexibility to draw diagrams, include premade pictures, and copy and paste information from various sources.

However, what I found is that I rarely looked back through my notes

My style is to use one notebook for multiple subjects which made each interspersed with another. This was prevented it from being useful as a resource when studying. Now, granted this isn’t the best method and maybe simply changing to a better organizational strategy may have helped.

However, I saw the iPad as a way to simply reduce the friction of going back through my notes. As James Clear says in Atomic Habits, this is the most important step to encourage a specific behavior.

I also wanted a device that would be able to run fore flight, which pushed me towards the iPad as opposed to the Thinkpad.

I didn’t want a laptop replacement, not at all. I do a lot of multitasking with an absurdly large amount of chrome tabs open researching multiple topics, having multiple desktops spread across multiple days of work and thoughts on different topics; for this I have a Thinkpad with 20 GB of RAM which suffices just fine.

Because I had this laptop already, I was much more willing to get an iPad as a secondary device for school.

What I didn’t realize about the iPad was that the limitations in multitasking actually proved to be a positive.

Using the keyboard case that Apple sells actually slows down my typing rate compared to the Thinkpad keyboard. However, the actual amount that I can write at a time has drastically increased. For me, I think it can be attributed to the terrible multitasking system on the iPad that actually forces me to focus.

At the end of the day, my justification for getting the iPad was quite simple — it makes doing the things that I already do easier. In particular, whenever I take notes I always use a pencil and paper. There’s a lot of evidence that shows improved understanding and retention when physically writing with you hand. However, the downside of this method as study revision when exam time come up. I almost never am able to go through my notes in an effective and timely manner, and this makes me put off studying until the last minute.

If you find yourself in a similar situation, then I think it is absolutely worth it. Moreover, I use the iPad extensively while flying. For these particular use cases, I feel that it is the perfect secondary device.

While of course I yearn for the iPad to run full blown macOS, and even more so now with the introduction of the M1 chip in the iPad, I do think that the specific limitations actually lend themselves extremely well to using the iPad in a very specific manner—it’s not meant to be a laptop replacement, but rather an augmentation—a secondary device where you need to focus on a specific task at a time. For this purpose the iPad is almost perfectly executed, especially with the new features for power users.