Winter mornings in New England are not a fun time to walk a half mile without knowing exactly where the hangar is. Walking past the fuel pump and over the wind swept snow piles of the airport apron, we paid careful attention to the numbers on the hangar doors. The blistering cold wind swept through the gaps of our jackets, sapping away what heat we had in our ears and fingers. We breathed a sigh of relief once we got to the right row and quickly rushed in to get shelter from the wind. That walk was brutal.

Pushing the little door open, we were greeted by the sight of the plane resting cozily inside. A small blue blanket covered the engine to keep it extra toasty. (It just looked so cute, 🙂 and now I really wish I took a picture! [Update: I finally got around to taking a picture of it!) The best part of it? The whole hangar was heated too! What a luxury to have a heated hangar to do our preflight in! While checking the oil, I could feel the heat emanating from the engine block and the smell of hot oil filled the air.

After doing the preflight and passenger briefing, we got ready to tow the plane out of the hangar and into the cold air. It took a few minutes to get the block heater and battery tender unplugged, the main hangar door open, attach the tow bar, and push the plane out. Then we had to get the hangar door closed again and get ourselves seated inside. All in, it was probably around 10 minutes or so from the door first opening.

I say all of this because, when it was time to start the engine, it wouldn’t start. The engine cranked and the prop spun for a few seconds, but nothing. I waited and tried again. And again. And again. This time, I waited a good 30 seconds before trying to let the starter cool down. I fiddled with the mixture and primer. Honestly, I thought we might have to scrub the flight and walk back to the terminal in the cold again! I told my passengers that this might happen, but that we should try a few more times.

Finally, I primed it one more time and leaned the mixture. Turning the key once again, and after a second or two of cranking, the engine finally came to life. Relief flooded the cockpit, and especially myself. I thought back to the first time I flew in this particular plane and we had a similar issue. That time, it took us quite a few tries to get the engine started and it made me nervous. I can only imagine what was going through the minds of my passengers today.

In hindsight, I probably should have familiarized myself with cold start procedures before the flight. I really thought that it would be a breeze with the engine block heater, but no — cold starting really is an art form.

It was only a day after 6 inches of snow fell in central Massachusetts. The whole landscape was covered in a layer of fresh, pure white snow. The timeline here may be confusing, as I flew again later in the day. I will intersperse elements from both flights in the story. But we pick up here at the beginning of the next flight.

For the second flight of the day, we needed to fuel up. I’m used to taxiing up to the self serve fuel, but at this airport, the fuel is full service. We called up the FBO and requested fuel at the hangar. By the time they got there, we had towed the plane out — this time leaving the cute little blanket on the engine to keep it warm and toasty! (I smile every time I think about this. . . 🙂)

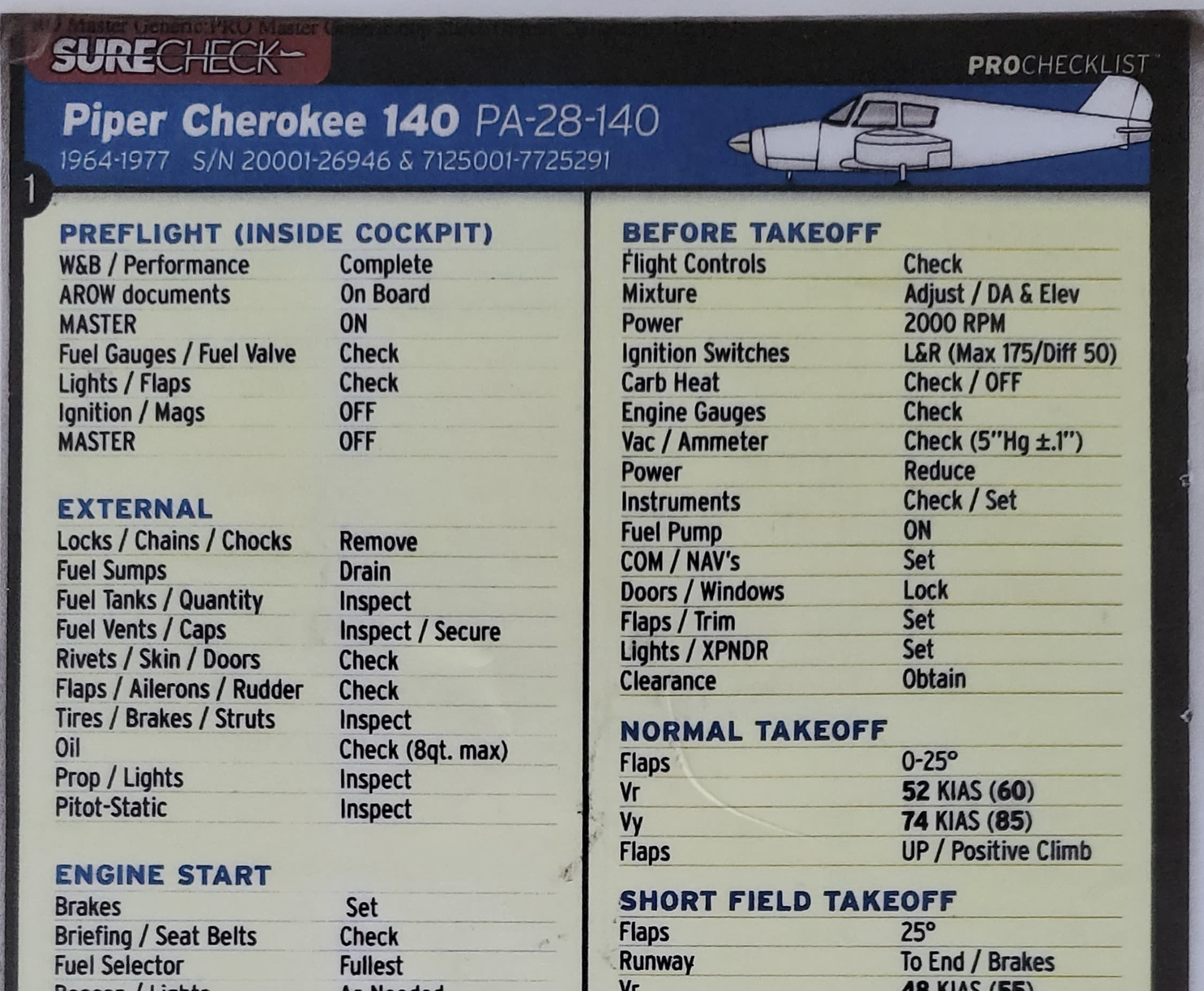

Quite a bit easier than having to top up the tanks ourselves! I didn’t think to discuss the leaded fuel with my passengers. After fueling and closing the hangar door, we all hopped on board and got ready to fly. I reviewed the preflight check and realized, whoops, I forgot to sump the fuel. After all the difficulty I had with starting the engine on the earlier flight and the brisk weather, I was seriously tempted to forgo sumping the tanks.

A few seconds later, I snapped out of it. I got out of the plane and checked the fuel tanks for water or other contaminants. It took less than a minute to do that. I scold myself now for even thinking about skipping the fuel check.

We eventually got the engine started. A bit quicker than the morning flight, I might add. Now feeling much more confident, it was easy going towards the city for some sight seeing. Worcester is a Class D airport, meaning that in order to enter, we need to establish two way radio communication. While we don’t need permission to do a city tour, per se, it is good to let the tower know what you’re planning to do. We radioed up Tower and let them know our intentions and were approved.

Overflying the city was beautiful, only intensified by the effusive sunset glow.

During the flight, I made sure to ask my passengers how they were doing several times throughout the flight. Key to this was asking them to rate their feeling on a scale of 1 to 10. This helps bring some objectivity into it. Many people, myself included, report that they’re doing fine even if they’re feeling slightly motion sick or tired. It’s not so bad that they feel the need to change the status from “okay.” As pilots, this is not a good situation. It means that passengers are not comfortable. This is a tip I learned from Flight Chops.

Funny story, I forgot to switch on the heat! I didn’t realize until half way when it got quite cold in the cockpit. At least we were all wearing jackets 😛